Lee Heinen: Body Language (I am not a Camera)

By Douglas Max Utter

In a world all but paved over with computer file-generated images, many visual artists continue to make representations of the world and themselves with traditional materials. Objective painting, in particular, appeals to the mind and heart in ways that elude digital assimilation. At the same time, painters manage to enrich their own projects with the ever-increasing sophistication, speed, and ease of contemporary imaging. Over the past few decades Cleveland-based painter Lee Heinen has used personal and notational photographs as a basis for her own ongoing renditions of people, places, and things. For a long time most of these were Kodak-type snapshots, but more recently smartphone photos and especially “selfies” have come into play, forming the basis for a recent, still ongoing series that is also inspired by travels to Thailand and China, and to England. These paintings, featuring tourists and their phones in modern translation, sometimes depict immemorial human foibles and self-delusion, but also uncover touches of cosmic grace. Whether working from family photographs taken decades ago, or from last month’s digital shots, Heinen rearranges poses and subject choices, using them as templates for apparent reminiscences which function as formal compositions, and as psychological journeys.

“Picnic” (2013) shows two adult women and a child at a wooden plank table with attached benches. They seem like people we might have known, family members perhaps, and yet they feel unreachable, reproducing the impact of old photographs. These may be people the painter actually is related to, but what matters is that this scene declares itself to be a part of the past. The child’s face, peaking shyly from behind his mother’s(?) dress, is merely a blank white form, while the women’s features are sketched tentatively, abandoned to time by a memory that has begun to lose some of its resolution. Still, the colors haven’t faded, nor the way that the younger woman stands and leans slightly over a bowl, stirring or scooping with an invisible spoon. In the forefront of this triangular composition, driven down and to the right by the brown lines of the table and bench, is the seated figure of an older woman. Probably she is the grandmother here, we can tell from her large white buttons, snaking in a sinuous line from the bottom of the canvas to her neck, a dotted line perforating the black oblong of her coffin-like dress. While this woman’s features are vague, and her eyes obscured by spectacles, her posture carries its own message. Her arms are crossed, her shoulders slumped. A viewer might feel that she is discouraged, tired, guarded. But then, this is not a painting of a memory, after all; this is a rendition of a photograph, edited, much-simplified, and altered in fundamental ways in order to make a formal/expressive image which reflects the artist herself. Perhaps, among other things, a painting can be considered an analog recording of perceptions (the surrealist-oriented abstract expressionists thought so) – an ancient concoction which also engages the viewer on a visceral level. A photograph, on the other hand, documents conditions of light and the attributes of the machine that generates it, and the process employed in printing it. Only down the road from these considerations is it about the objects pictured, and (at last) about a photographer’s choice of subject matter.

“Picnic” (2013) shows two adult women and a child at a wooden plank table with attached benches. They seem like people we might have known, family members perhaps, and yet they feel unreachable, reproducing the impact of old photographs. These may be people the painter actually is related to, but what matters is that this scene declares itself to be a part of the past. The child’s face, peaking shyly from behind his mother’s(?) dress, is merely a blank white form, while the women’s features are sketched tentatively, abandoned to time by a memory that has begun to lose some of its resolution. Still, the colors haven’t faded, nor the way that the younger woman stands and leans slightly over a bowl, stirring or scooping with an invisible spoon. In the forefront of this triangular composition, driven down and to the right by the brown lines of the table and bench, is the seated figure of an older woman. Probably she is the grandmother here, we can tell from her large white buttons, snaking in a sinuous line from the bottom of the canvas to her neck, a dotted line perforating the black oblong of her coffin-like dress. While this woman’s features are vague, and her eyes obscured by spectacles, her posture carries its own message. Her arms are crossed, her shoulders slumped. A viewer might feel that she is discouraged, tired, guarded. But then, this is not a painting of a memory, after all; this is a rendition of a photograph, edited, much-simplified, and altered in fundamental ways in order to make a formal/expressive image which reflects the artist herself. Perhaps, among other things, a painting can be considered an analog recording of perceptions (the surrealist-oriented abstract expressionists thought so) – an ancient concoction which also engages the viewer on a visceral level. A photograph, on the other hand, documents conditions of light and the attributes of the machine that generates it, and the process employed in printing it. Only down the road from these considerations is it about the objects pictured, and (at last) about a photographer’s choice of subject matter.The painted interlocking shapes that compose “Picnic” are influenced by stenciling and collage works, and its off balance, thrusting energies derive from a lineage of design traceable at least as far back as Japanese Ukiyo-e woodcuts. Heinen proposes: three human figures, a table with attached benches, a bowl, a bird, the spear-like leaves of irises at the foundation of a house, a window, and a door. The figures are awkward, in the way that paper dolls can be, their clothes bulge and peak, the seated woman’s hat is a peculiar affair, like a tiny thatched roof – yet all of these mildly odd, vaguely child-like features recall remote Japonisme-influenced figurative drawings and paintings (Vincent Van Gogh, and expressive symbolists such as Edvard Munch and James Ensor) and the over-stuffed quality of the “past,” an impression of obsolete exaggeration.

But the postures — the body language as Heinen says, brings these sketchy forms to life in unexpected ways, modulating the design of her composition with qualities of mood and character. The older woman in her dark, old-fashioned dress reads as isolated and depressed, separated from her grandchild by the younger woman (to presume these relationships), who is dressed in the fleshy pink of youth. The bowl in this young mother’s hands conveys her vital, nourishing role, an idea reinforced by the blue bird which feeds from it. The bird itself is an interpolation, and surely Heinen means it to be an obvious one – as if to say,”Do you believe in fairy tales? Then here’s a bluebird.” “Picnic” is about inevitable envy and pain, as roles are transferred and family dynamics roll forward.

As an artist who, like Lee Heinen, has lived much of his life in the long shadow of the Cleveland Museum of Art, I am also attracted to “Picnic” because of a certain similarity that its composition and figures share with those of a very prominent work in CMA’s collection. Fairfield Porter’s large 1967 pastoral painting “Nyack” also foregrounds an older, plainly depressed female figure, contrasting her downward gazing posture with the vigor of a younger woman, who paints at an easel in the middle distance. Both are seated under a large tree, the older woman in a long, colorful, traditional folk-style skirt, the artist in a formal black skirt and dark brown, sleeveless top. In costume they are almost the reverse of Heinen’s figures, but the mood and subliminal message strike a related chord. And Heinen’s picnic table ties her composition together with a single strong movement, just as the angled, broken arc of benches and easel in Porter’s work leads the eye back and forth, like a swing across his big canvas. It’s worth noting also that “Nyack” was based on a much earlier sketch the artist had made, rather than on a photograph, and that his wife was one of the figures (the elder), and the other was a friend. But in both works there is a disquieting sense that some stylistic and compositional choices expressing calm and continuity are at odds with specters of personal or interpersonal dissatisfaction, which haunt these superficially blithe paintings through body language and surprisingly dynamic internal organization.

Among the most strongly conceived of Heinen’s recent paintings is “The Mango Thief” (2015). The title refers to a baboon, grinning for the cameras and iphones of a group of amused tourists, who seem as greedy for a photo-op as the baboon is for the small mangos, which spill out over the yellow ground from a white paper bag. These complicit observers include the artist herself, of course, who clicked her own pic of the scene during a recent trip to Thailand. She later tweaked the elements of that photo to make her painting, which plays the shapes and colors of its five characters against a yellow background like a musical progression, harmonizing tones of pink, orange, pale green and blue-gray with the white-spangled maroon of the dress worn by a strong central figure. That woman, in seamed silk stockings and deep yellow sun-hat, is pictured from the back, as are the two tourists who occupy the left side of the canvas. At the bottom left corner a man crouches to get the best angle. His baseball cap is on backwards, making room for the black point-and-shoot that he holds to his face. Nearest to the monkey, a young woman wields a blue smartphone. She wears a leaf green shirt, sleeves rolled to her elbows, untucked above bone-colored chinos. Her weight rests casually, confidently on one hip, her blonde hair reaches down from under a bucket-shaped hat. A jaunty brown strap crosses her back from shoulder to waist, as if she was on a military expedition, or a Girl Scout ramble; and her shoes match her phone. Probably she and the young man are together. We see only part of the side of her face, just a crescent of light pink cheek, but her slim, fit, not quite stylish look suggests that, though young she’s no longer a girl. Across from her a figure with glasses and a short haircut is rendered in an all-over pale bluish gray. Perhaps he’s in shadow, although if so the shade is confined to his own outline. It’s more that he’s part of the back story – he’s the mango vendor, maybe, from whom the baboon snatched the bag of fruit. He holds up one hand in admonition or entreaty. Or maybe he’s just a cool passage of shadow on a hot day.

Among the most strongly conceived of Heinen’s recent paintings is “The Mango Thief” (2015). The title refers to a baboon, grinning for the cameras and iphones of a group of amused tourists, who seem as greedy for a photo-op as the baboon is for the small mangos, which spill out over the yellow ground from a white paper bag. These complicit observers include the artist herself, of course, who clicked her own pic of the scene during a recent trip to Thailand. She later tweaked the elements of that photo to make her painting, which plays the shapes and colors of its five characters against a yellow background like a musical progression, harmonizing tones of pink, orange, pale green and blue-gray with the white-spangled maroon of the dress worn by a strong central figure. That woman, in seamed silk stockings and deep yellow sun-hat, is pictured from the back, as are the two tourists who occupy the left side of the canvas. At the bottom left corner a man crouches to get the best angle. His baseball cap is on backwards, making room for the black point-and-shoot that he holds to his face. Nearest to the monkey, a young woman wields a blue smartphone. She wears a leaf green shirt, sleeves rolled to her elbows, untucked above bone-colored chinos. Her weight rests casually, confidently on one hip, her blonde hair reaches down from under a bucket-shaped hat. A jaunty brown strap crosses her back from shoulder to waist, as if she was on a military expedition, or a Girl Scout ramble; and her shoes match her phone. Probably she and the young man are together. We see only part of the side of her face, just a crescent of light pink cheek, but her slim, fit, not quite stylish look suggests that, though young she’s no longer a girl. Across from her a figure with glasses and a short haircut is rendered in an all-over pale bluish gray. Perhaps he’s in shadow, although if so the shade is confined to his own outline. It’s more that he’s part of the back story – he’s the mango vendor, maybe, from whom the baboon snatched the bag of fruit. He holds up one hand in admonition or entreaty. Or maybe he’s just a cool passage of shadow on a hot day.But despite these characters and the gentle swirl of visual information they present, this is a painting that derives its real strength from the startling, even ravishing swathe of abstract chaos seen through the maroon window which is the central figure’s patterned dress. The figures that circle around her, up toward the baboon facing them all, are present not because of the photo-op, but because they orbit this patch of pure freedom that attracts them, and the eye of the viewer, irresistibly. The batik-like white slashes and suns explode the painting’s anecdotal and reflective narratives (its thoughts about presence and identity and perspective) as if the sunny street scene were split open like a fruit, to reveal the energy of worlds. It’s just a glimpse, but a mighty one, presented so deftly that at first it’s hard to see, and afterwards all but sets fire to the remainder of the painting, in the manner of an E.M. Forster-like revelation/event. Yet while this abstraction (which must represent a decorative floral motif, yet becomes so vitally changed, and charged, on the canvas) crashes into the painting like a starship, it harmonizes with the other tones and shapes, and with the cloisonnism of Heinen’s delicate outlines, pushing only gently against the boundaries that it nevertheless destroys. If the baboon has stolen and (with Henri Rousseau-ish delight) devours the raw sunshine of unself-conscious experience, which we tourists then steal from the grinning animal with our devices, it remains true that the outrageous splash of Being spreads throughout and beyond any style, anecdote, or captivity, contained only tenuously before the god returns to claim its own.

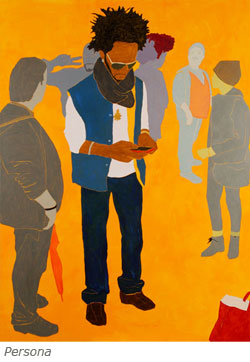

“Persona,” also composed from smartphone photos, is a more straightforward look at the way the distractions of technology alter our common experience of public space, going on to comment about deeper social issues. A young man, African-American with an intensely theatrical vibe, with golden-brown skin and a spiking corona of dark hair that rises from his broad, downturned forehead — almost as if he were in costume as the Sun itself — dominates the canvas. The power that he emanates is a matter of both composition and personality – it’s clear that he is the “persona” of the title, a self-realized and at this moment self-absorbed, somewhat larger-than-life individual, depicted as he quite literally stands out in a crowd while communing with his smartphone. He eclipses the plump gray, probably Caucasian figure beside him, who wears a thigh-length hooded jacket and carries a furled orange umbrella. On the other hand, he seems to emit the three gray-toned people depicted behind his huge head, since their lower bodies disappear behind his shoulders. Another man with a mustache stands beyond him on the right, appearing to lock eyes across the canvas with the paunchy man on the left; the faces just behind the “sun” man are looking to the right. Lastly, a sixth figure on the right is turned toward the upper left. The sun-man/cell man’s head is the center point where each sight line intersects all the others. People in their orbits see him; he does not trouble to see them. The painting could be titled: “Solar System.”

“Persona,” also composed from smartphone photos, is a more straightforward look at the way the distractions of technology alter our common experience of public space, going on to comment about deeper social issues. A young man, African-American with an intensely theatrical vibe, with golden-brown skin and a spiking corona of dark hair that rises from his broad, downturned forehead — almost as if he were in costume as the Sun itself — dominates the canvas. The power that he emanates is a matter of both composition and personality – it’s clear that he is the “persona” of the title, a self-realized and at this moment self-absorbed, somewhat larger-than-life individual, depicted as he quite literally stands out in a crowd while communing with his smartphone. He eclipses the plump gray, probably Caucasian figure beside him, who wears a thigh-length hooded jacket and carries a furled orange umbrella. On the other hand, he seems to emit the three gray-toned people depicted behind his huge head, since their lower bodies disappear behind his shoulders. Another man with a mustache stands beyond him on the right, appearing to lock eyes across the canvas with the paunchy man on the left; the faces just behind the “sun” man are looking to the right. Lastly, a sixth figure on the right is turned toward the upper left. The sun-man/cell man’s head is the center point where each sight line intersects all the others. People in their orbits see him; he does not trouble to see them. The painting could be titled: “Solar System.” But Heinen’s main cell phone painting (to date) depicts this sort of public narcissism as a mass pictorial phenomenon, rather than soliloquy. “Selfies” (2015) is composed horizontally in what computer programs call landscape mode; there are enough portraits going on here already — eight individuals and one couple are shown recording themselves. Oat one point the level horizon line gives rise to a shadowy outline of Rodin’s The Thinker, pedestaled in gray.This is clearly the Cleveland Museum of Art’s bronze edition of that famous work, mutilated by explosives in 1970 and reinstalled in its damaged state as a grim reminder of humanity’s ongoing irrationality. Its presence establishes a sort of mise en scene, but one more psychological than literal.

But Heinen’s main cell phone painting (to date) depicts this sort of public narcissism as a mass pictorial phenomenon, rather than soliloquy. “Selfies” (2015) is composed horizontally in what computer programs call landscape mode; there are enough portraits going on here already — eight individuals and one couple are shown recording themselves. Oat one point the level horizon line gives rise to a shadowy outline of Rodin’s The Thinker, pedestaled in gray.This is clearly the Cleveland Museum of Art’s bronze edition of that famous work, mutilated by explosives in 1970 and reinstalled in its damaged state as a grim reminder of humanity’s ongoing irrationality. Its presence establishes a sort of mise en scene, but one more psychological than literal.For one thing, each figure or pair of figures is a different size. It’s as if they occupy different, invisibly intersecting planes, collaged together here but foreign to one another in fact – no Euclidean law unifies this un-space, no classical perspective. The characters themselves are variously equipped, some with selfie-sticks, some without, and have different ideas about how to depict themselves. One woman puts her phone on the ground and crouches over it, like Narcissus at his pond. Two others resemble duelists when their sticks cross as they try to frame a more distant view – though this is less a clash than an optical illusion, since they appear to belong in different decades, in different frames of reference entirely. There can be no crossing of gazes or sightlines in this strange land, where all regard is self-regard and the eye bends back toward itself at the crook of the selfie-stick. Several of the amateur photographers shown wear dark glasses, which also speaks of their isolation, if not their blindness. One of these is the artist herself, whose hand and face (depicted on a phone display) are painted in the lower left-hand corner of the canvas. This moment of friendly self-caricature takes a little of the sting out of a work which otherwise carries a sharp satirical message. If the wreck of reason as symbolized by Rodin’s sculpture is the emblem of the situation she considers here, the inclusion of a self-portrait alerts us to the thought that the artist, working to assemble these vignettes, is making a kind of parable painting, a rich genre with roots in medieval manuscript illustrations. Heinen is a student of historical manners and the artistic triumphs of western art, and her awareness in “Selfies” of the incomparably resourceful, socially acerb masterpieces of Pieter Breugel the Elder is clear. Breugel’s “Parable of the Blind” comes to mind, and the “Land of Cockaigne.” Heinen’s contribution to this genre could be called, “Wherever We Go We Find Ourselves.”

A third work from 2015 is titled, “The Changing of the Guard,” based on a photograph taken by Heinen during a visit to London. Buckingham Palace doesn’t appear in her painting, and neither does the Queen, nor the guards. This time the iphones themselves play a major compositional role, piercing the horizontal canvas like darkened windows. Not that there’s necessarily anything negative about her conception here. Her light touch and mostly pale pastel tones, seen also in her symbolist-related sea and shore ‘scapes, reflect an American lineage of modernist and proto-modernist depiction that includes Milton Avery, Albert Pinkham Ryder, and Marsden Hartley. “The Changing of the Guard” feels more like an abstract work than Heinen’s other camera-phone paintings. Open space plays an important design role in those pieces, sometimes in terms of color (the burning yellow ground asserts itself throughout “Persona,” stoking the solar imagery), or as a sort of narrative neutrality, like the putty-colored no-man’s land between the figures in “Selfies.” In the London painting we see a finely composed patchwork woven from the backs of heads and a tangle of forearms, sleeves, hands, which hold the rectangles that only living generations would recognize as cameras, and a stripe of warm gray at the top of the canvas. No pageant, no crimson uniforms, no military headgear, just the jostle of the moment, the elbows of the photo-op, and a few telling details: a watch (with hands) reporting the time on one man’s wrist, and right in the middle of the canvas a blank cell phone display surrounded by a black and white striped border. This signage perhaps declares or even celebrate the absence of an external referent, a subject for the mayhem of recording. The blankness of all the little screens (parts of ten are shown) imposes its own message, at least, along with the omission of spectacle: there is nothing to see here, except perhaps ourselves turning away from contact; the contemporary gesture of presence, marking each occasion with a photograph, cancels out experience and makes reality moot.

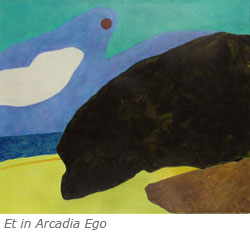

A third work from 2015 is titled, “The Changing of the Guard,” based on a photograph taken by Heinen during a visit to London. Buckingham Palace doesn’t appear in her painting, and neither does the Queen, nor the guards. This time the iphones themselves play a major compositional role, piercing the horizontal canvas like darkened windows. Not that there’s necessarily anything negative about her conception here. Her light touch and mostly pale pastel tones, seen also in her symbolist-related sea and shore ‘scapes, reflect an American lineage of modernist and proto-modernist depiction that includes Milton Avery, Albert Pinkham Ryder, and Marsden Hartley. “The Changing of the Guard” feels more like an abstract work than Heinen’s other camera-phone paintings. Open space plays an important design role in those pieces, sometimes in terms of color (the burning yellow ground asserts itself throughout “Persona,” stoking the solar imagery), or as a sort of narrative neutrality, like the putty-colored no-man’s land between the figures in “Selfies.” In the London painting we see a finely composed patchwork woven from the backs of heads and a tangle of forearms, sleeves, hands, which hold the rectangles that only living generations would recognize as cameras, and a stripe of warm gray at the top of the canvas. No pageant, no crimson uniforms, no military headgear, just the jostle of the moment, the elbows of the photo-op, and a few telling details: a watch (with hands) reporting the time on one man’s wrist, and right in the middle of the canvas a blank cell phone display surrounded by a black and white striped border. This signage perhaps declares or even celebrate the absence of an external referent, a subject for the mayhem of recording. The blankness of all the little screens (parts of ten are shown) imposes its own message, at least, along with the omission of spectacle: there is nothing to see here, except perhaps ourselves turning away from contact; the contemporary gesture of presence, marking each occasion with a photograph, cancels out experience and makes reality moot. It seems to me that existential reflections are very much built into Lee Heinen’s recent paintings, and can be found in the larger body of work she has produced over the last two or three decades. No doubt her work carries other, less fraught messages as well, and it is very possible to look at her scenes and people in a more relaxed state of mind. She is a remarkable colorist, and almost without exception her paintings appeal to the eye, often with a warmth that encourages the viewer to look longer, to remain in her painted places. Yet often the result of this is that she has time to show us other things, darker moods. Her 2013 work “Et in Arcadia Ego” is attractive in this way, presenting a hidden strip of beach, where masses of rock move down to the shore. It is a place many people would find appealing, promising both beauty and solitude. But the orb overhead announces a more exceptional condition: Either a solar or lunar eclipse is in progress. Is this then a nocturne, in the manner of Ryder or Avery? And there is the fact that the central massive boulder is painted a stark black, as it slouches toward the deep blue water across the sand. The viewer is caught between the pleasures of this composition, and an ominous note too loud to be ignored. The title should have warned us: “Et in Arcadia Ego” is a line thought to derive from the Eclogues of the Roman poet Vergil, declaring a subject approached by Poussin and Guercino, among others. It literally means, “And in Paradise I,” which is usually taken to remind us that death can be found everywhere, though the ambiguity of the phrase has been much discussed over the centuries. I think that Heinen uses it more as a title than a phrase, explicitly including her image in a group of historical works which contemplate death as a fact of life, as with memento mori paintings. In Heinen’s painting, however, there is a dramatic impact that needs no interpretive gloss. This conspiracy of elements, of light and dark, under the dark lantern of a moon in celestial shadow, is legible only as romance. Heinen’s work partakes of mystery and the old promise of treasures abandoned on an incoming tide.

It seems to me that existential reflections are very much built into Lee Heinen’s recent paintings, and can be found in the larger body of work she has produced over the last two or three decades. No doubt her work carries other, less fraught messages as well, and it is very possible to look at her scenes and people in a more relaxed state of mind. She is a remarkable colorist, and almost without exception her paintings appeal to the eye, often with a warmth that encourages the viewer to look longer, to remain in her painted places. Yet often the result of this is that she has time to show us other things, darker moods. Her 2013 work “Et in Arcadia Ego” is attractive in this way, presenting a hidden strip of beach, where masses of rock move down to the shore. It is a place many people would find appealing, promising both beauty and solitude. But the orb overhead announces a more exceptional condition: Either a solar or lunar eclipse is in progress. Is this then a nocturne, in the manner of Ryder or Avery? And there is the fact that the central massive boulder is painted a stark black, as it slouches toward the deep blue water across the sand. The viewer is caught between the pleasures of this composition, and an ominous note too loud to be ignored. The title should have warned us: “Et in Arcadia Ego” is a line thought to derive from the Eclogues of the Roman poet Vergil, declaring a subject approached by Poussin and Guercino, among others. It literally means, “And in Paradise I,” which is usually taken to remind us that death can be found everywhere, though the ambiguity of the phrase has been much discussed over the centuries. I think that Heinen uses it more as a title than a phrase, explicitly including her image in a group of historical works which contemplate death as a fact of life, as with memento mori paintings. In Heinen’s painting, however, there is a dramatic impact that needs no interpretive gloss. This conspiracy of elements, of light and dark, under the dark lantern of a moon in celestial shadow, is legible only as romance. Heinen’s work partakes of mystery and the old promise of treasures abandoned on an incoming tide.Whether she is exploring and re-defining landscape in fauvist terms of energy and symbol and intense color, as she did a few years ago, or delving into the sociological revelations of photography, especially in its latest instant incarnations, mixing these resources into her own rich sense of art history, Heinen is unfailingly a painter with a deeply human touch. Her work is less a matter of immediate call and response, reacting to the lived reality of day to day existence, than a measured participation in a visual artist’s constantly, rapidly expanding worlds of imagery and mediums. Her humanity resides most in the warmth of her considerations of the people and things she depicts, and a sense in her paintings that these personae and elements are part of the pattern of her life, translated from secret tongues of experience known to herself alone. This is, after all, how we make the present moment rich in spirit, through a willingness to relate, re-examine, re-tell our own past.